Kolbert Sixth Extinction

The plight of doomed, extinct or nearly extinct animals is embodied in Elizabeth Kolbert’s arresting new book, “The Sixth Extinction,” by two touching creatures. Suci, a 10-year-old Sumatran rhino who lives at the Cincinnati Zoo, is one of the few of her endangered species to be “born anywhere over the past three decades.” Efforts by her caregivers to get her pregnant through artificial insemination, Ms. Kolbert reports, have been complicated because female Sumatrans are “induced ovulators”: “They won’t release an egg unless they sense there’s an eligible male around,” and “in Suci’s case, the nearest eligible male is ten thousand miles away.” A Hawaiian crow (or alala) named Kinohi, one of maybe a hundred of his kind alive today, was born at a captive breeding facility more than 20 years ago and now lives at the San Diego Zoo. He is described as an odd, solitary bird, who does not identify with other alala, and has refused to mate with other captive crows, despite his human caregivers’ hope that he will contribute to his species’ limited gene pool. “He’s in a world all to himself,” the zoo’s director of reproductive physiology said of Kinohi. “He once fell in love with a spoonbill.” Photo.

Advertisement Ms. Kolbert wrote a lucid, chilling 2006 book about (“”), and in “The Sixth Extinction,” she employs a similar methodology, mixing reporting trips to far-flung parts of the globe with interviews with scientists and researchers. Her writing here is the very model of explanatory journalism, making highly complex theories and hypotheses accessible to even the most science-challenged of readers, while providing a wonderfully tactile sense of endangered (or already departed) species and their shrinking habitats. She writes as a popularizer — or interpreter — of material that has been excavated by an army of scientists over the years and, in many cases, mapped by earlier writers. Her book covers some ground that will be familiar to readers of books like “” by David Quammen, “” by Scott Weidensaul and the writings of the biologist Edward O. It even borrows the title of a 1995 book by Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin, which also addressed the story of the previous five mass extinction events and the human role in the so-called sixth.

The tireless Ms. Kolbert hikes through a Peruvian forest, where “the trees were not just trees; they were more like botanical gardens, covered with ferns and orchids and bromeliads and strung with lianas.” Here, her guide is a forest ecologist named Miles Silman, who’s been looking at how global warming restructures ecological communities. She meets with the atmospheric scientist Ken Caldeira, known for his pioneering work in ocean acidification (changing pH levels in seawater brought about by the absorption of growing levels of carbon dioxide), on the Great Barrier Reef off Australia and gives us a succinct — and scary — assessment of the deadly effect that growing acidity and rising temperatures are having on coral reefs (which, in turn, help support “thousands — perhaps millions — of species” directly or indirectly). Solomat Mpm 500e Manual Transmission. Suci, a 10-year-old Sumatran rhino at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Ryuichi Sakamoto Rain Pdf Reader. Feb 16, 2014 In lucid prose, she examines the role of man-made climate change in causing what biologists call the sixth mass extinction — the current spasm of plant and animal loss that threatens to eliminate 20 to 50 percent of all living species on earth within this century. Extinction is a relatively new idea in the scientific community.

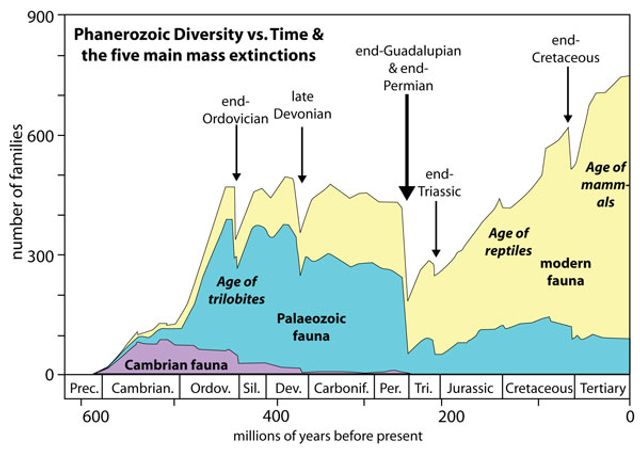

Credit Al Behrman/Associated Press In another chapter, about the spread of (hastened by human travel and commerce), she investigates the case of a sudden bat die-off in New York and New England, brought about a cold-loving fungus that was “accidentally imported to the U.S., probably from Europe.” Accompanying wildlife and conservation experts on a hike into the chilly depths of Aeolus Cave in Vermont, she sees there a kind of bat hell — thousands of dead and dying bats littering the frozen ground, many of them crushed and bleeding underfoot. Kolbert is nimble at using such dramatic scenes to make sense of larger ideas. Libronix Serial Keygenreter here. In the course of this volume, she traces the history of human understanding of the concept of extinction (which first developed thanks largely to the animal now known as the American mastodon and the work of the naturalist Georges Cuvier in revolutionary France), and she describes how the understanding of annihilation by catastrophe modified the Darwinian concept of survival of the fittest. Whether it was the giant asteroid that took out the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period (one geologist says, “Basically, if you were a triceratops in Alberta, you had about two minutes before you got vaporized”) or the glaciation believed to have brought an end to the Ordovician period, catastrophes have the effect of fundamentally altering the rules of the survival game. “Traits that for many millions of years were advantageous all of a sudden become lethal,” Ms. Kolbert writes, adding that it may be “the very freakishness of the events” that made them so deadly, forcing organisms to contend with conditions for which they were “evolutionarily, completely unprepared.” Today’s deadly change agent, Ms.